Introduction

From (Kalpakjian & Schmid, 2016):

The various microstructures developed during metal processing can be modified by heat treatment techniques, involving controlled heating and cooling of the alloys at various rates.

The relevant chapters in Intro to Material Engineering are IMT1_004, IMT1_005 and IMT1_006.

Heat Treating Ferrous Alloys

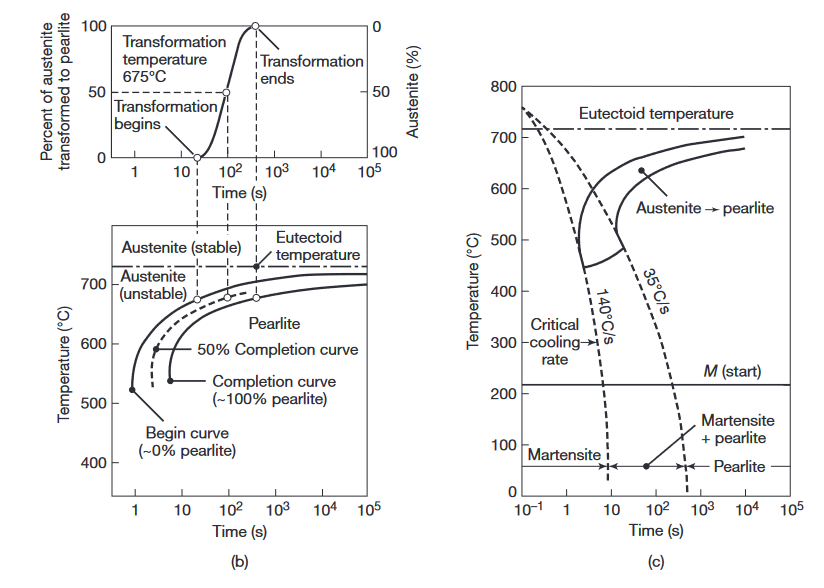

(a) Austenite to pearlite transformation of iron-carbon alloys as a function of time and temperature. (b) Isothermal transformation diagram obtained from (a) for a transformation temperature of

. (c) Microstructures obtained for a eutectoid iron-carbon alloy as a function of cooling rate.

Tempered martensite:

Tempering is a heating process that reduces martensite’s hardness and improves its toughness. The body-centered tetragonal martensite is heated to an intermediate temperature, where it transforms to a two-phase microstructure, consisting of body-centered cubic alpha ferrite and small particles of cementite. Longer tempering time and higher temperature decrease martensite’s hardness. The reason is that the cementite particles coalesce and grow, and the distance between the particles in the soft ferrite matrix increases as the less stable, smaller carbide particles dissolve.

Austenitization:

Austenitization means to heat the iron, iron-based metal, or steel to a temperature at which it changes crystal structure from ferrite to austenite.

Quenching:

Quenching may be carried out in water, brine (saltwater), oils, molten salts, or air, as well as caustic solutions, polymer solutions, and various gases. Because of the differences in the thermal conductivity, specific heat, and heat of vaporization of these media, the rate of cooling also will be different.

Heat Treating Nonferrous Alloys and Stainless Steels

Nonferrous alloys and some stainless steels generally cannot be heat treated by the techniques for ferrous alloys, because nonferrous alloys do not undergo phase transformations as steels do. Heat-treatable aluminum alloys, copper alloys, and martensitic and precipitation-hardening stainless steels are hardened and strengthened by precipitation hardening. This is a technique in which small particles of a different phase (called precipitates) are uniformly dispersed in the matrix of the original phase. Precipitates form because the solid solubility of one element (one component of the alloy) in the other is exceeded.

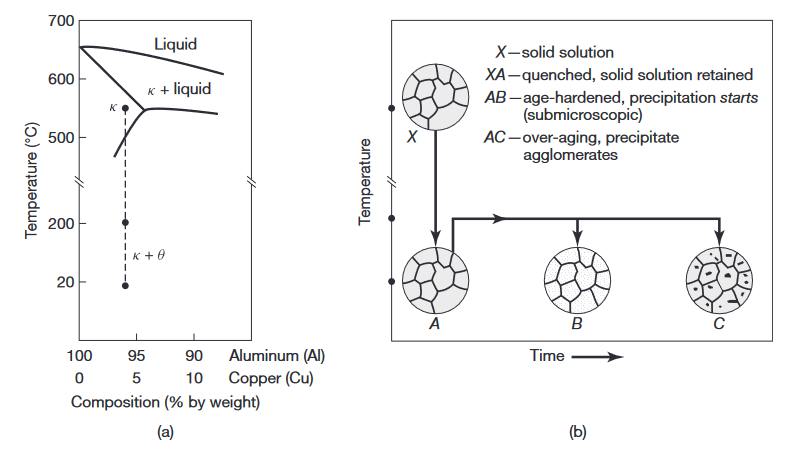

(a) Phase diagram for the aluminum-copper alloy system. (b) Various microstructures obtained during the age-hardening process (Kalpakjian & Schmid, 2016).

Solution treatment:

In solution treatment the alloy is heated to within the solid-solution

Precipitation hardening:

The structure obtained in

Aging:

Because the precipitation process is one of time and temperature, it is also called aging, and the property improvement is known as age hardening. If carried out above room temperature, the process is called artificial aging. Several aluminum alloys harden and become stronger over a period of time at room temperature, by a process known as natural aging.

These alloys are first quenched and then, if required, are formed at room temperature into various shapes, and allowed to develop strength and hardness by natural aging. Natural aging can be slowed by refrigerating the quenched alloy.

In the precipitation process, as the reheated alloy is held at that temperature for an extended period of time, the precipitates begin to coalesce and grow. They become larger but fewer, as shown by the larger dots in

Exercises

Question 1

Consider the following microstructures and conclude about:

- Heat treatment done on the mentioned material – type and approximate regime.

- Mechanical properties – tensile strength, ductility, fracture toughness (high/low).

- Possibility to perform a bulk forming (yes/no) and why.

- If the following bulk forming is impossible, how to make it possible.

Part a

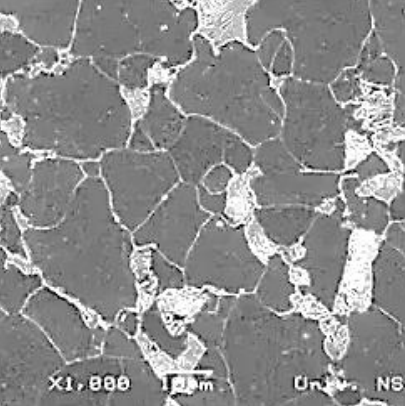

Aluminum based alloy 6061: intermetallic precipitates

Solution:

According to Heat Treating Nonferrous Alloys and Stainless Steels:

- Solution treatment (approximately at

) and then aging (approximately ) heat treatment. - Strength – high, ductility – low, fracture toughness – medium.

- No possibility for bulk forming due to low ductility (caused by precipitates).

- To perform bulk forming, precipitates should be dissolved in the matrix, so the material should be re-heated up to

and then subjected to solution treatment prior to a bulk forming

Part b

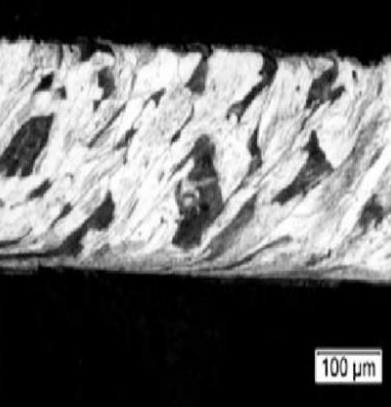

Low carbon steel 1020: (top) non-deformed grains structure; (bottom) plastic formed strongly elongated grains.

Solution:

According to Heat Treating Ferrous Alloys:

- Austenitization at approximately

followed by a slow cooling. - Mechanical properties – tensile strength medium, ductility high, fracture toughness high.

- There exists a possibility for cold and hot bulk forming – due to a high ductility and fracture toughness.

Question 2

Given the following diagrams

.png)

Isothermal transformation diagram for an iron–carbon alloy of eutectoid composition and the isothermal heat treatments for different treatments (Callister, 2007).

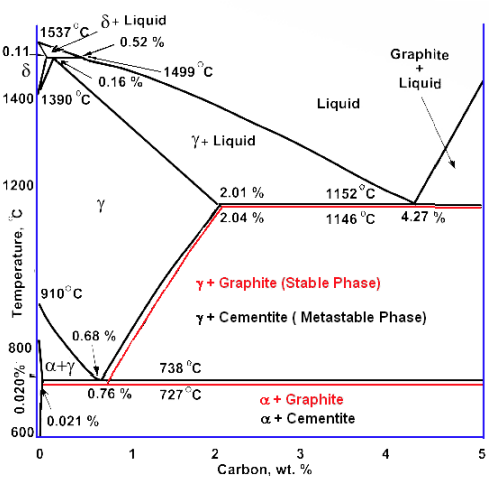

Iron-carbon phase diagram

Define which phases will compose the eutectoid steel’s microstructure if it will be heated to

- Rapidly cool to

hold for , and quench to room temperature. - Rapidly cool to

, hold for , and quench to room temperature. - Rapidly cool to

, hold for , rapidly cool to hold for , and hold for , and quench to room temperature.

Solution:

from (Callister, 2007):

- At austenite isothermally transforms to bainite; this reaction begins after about

and reaches completion at about elapsed time. Therefore, by , as stipulated in this problem, of the specimen is bainite, and no further transformation is possible, even though the final quenching line passes through the martensite region of the diagram. - In this case it takes about

at for the bainite transformation to begin, so that at the specimen is still austenite. As the specimen is cooled through the martensite region, beginning at about , progressively more of the austenite instantaneously transforms to martensite. This transformation is complete by the time room temperature is reached, such that the final microstructure is martensite. - For the isothermal line at , pearlite begins to form after about

; by the time has elapsed, only approximately of the specimen has transformed to pearlite. The rapid cool to is indicated by the vertical line; during this cooling, very little, if any, remaining austenite will transform to either pearlite or bainite, even though the cooling line passes through pearlite and bainite regions of the diagram. At , we begin timing at essentially zero time; thus, by the time have elapsed, all of the remaining austenite will have completely transformed to bainite. Upon quenching to room temperature, any further transformation is not possible inasmuch as no austenite remains; and so the final microstructure at room temperature consists of pearlite and bainite.