Introduction

From (Kalpakjian & Schmid, 2016):

Joining is a general, all-inclusive term covering numerous processes that are important in manufacturing. Joining may be preferred or necessary for one or more of the following reasons:

- The product is impossible or uneconomical to manufacture as a single piece;

- The product is easier and less costly to manufacture in individual components, which are then assembled;

- The product may have to be taken apart for repair or maintenance during its service life;

- Different properties may be required for function of the product; for example, surfaces that are subjected to friction and wear, or to corrosion and environmental attack, typically require characteristics different than those of the component’s bulk; and

- Transportation of the product in individual components and their subsequent assembly may be easier and more economical than transporting it as a single unit.

There are many categories of joining and fastening processes; In our course we will focus on welding and brazing and soldering.

| Topic | Subtopic | Details |

|---|---|---|

| Fusion Welding | Involves melting and coalescing materials by heat, typically using electrical or other means. | |

| Oxyfuel Gas Welding (OFW) | Developed in the early 1900s. Uses a fuel gas and oxygen to produce a flame for melting metals at the joint. | |

| Arc Welding Processes | Uses electrical energy to generate heat via an electric arc. Involves consumable or nonconsumable electrodes. | |

| Arc Welding Processes: Consumable Electrode | Shielded Metal Arc Welding (SMAW) | One of the oldest and most versatile processes. Generates an electric arc by touching and withdrawing a coated electrode. |

| Gas Metal Arc Welding (GMAW) | Shielded by an external gas source. Developed in the 1950s. Suitable for ferrous and nonferrous metals. Doubles welding productivity compared to SMAW. | |

| Arc Welding Processes: Nonconsumable Electrode | Gas Tungsten Arc Welding (GTAW) | Uses a nonconsumable tungsten electrode. Filler metal supplied from a filler wire. |

| Plasma Arc Welding (PAW) | Uses ionized hot gas (plasma) for welding. Greater energy concentration, better arc stability, less thermal distortion, and higher welding speeds compared to other arc welding processes. | |

| High Energy Beam Welding | Includes electron-beam welding (EBW) and laser-beam welding (LBW), which offer high quality and technical advantages in modern manufacturing. | |

| Electron-Beam Welding (EBW) | Heat generated by high-velocity, narrow-beam electrons, converting kinetic energy to heat upon striking the workpiece. | |

| Laser-Beam Welding (LBW) | Uses a high-power laser for heat, with deep penetrating capability suitable for deep and narrow joints. | |

| Oxyfuel–gas Cutting (OFC) | Similar to oxyfuel gas welding but used to remove a narrow zone from metal plates or sheets. | |

| Resistance Welding (RW) | Heat generated by electrical resistance between two joined members. | |

| Brazing and Soldering | Lower temperatures compared to welding. Brazing involves melting a filler metal placed between surfaces to be joined. |

The Fusion Welded Joint

Fusion welding is a process where the workpieces are joined by melting their edges together and adding filler material if necessary. This chapter focuses on the characteristics, advantages, and limitations of fusion welded joints.

Key Points:

- Strength and Defects: Fusion welded joints can be as strong as the base materials, but they are susceptible to defects like porosity, cracking, and residual stresses.

- Thermal Effects: The heat from welding can lead to significant thermal distortion and residual stresses, which may weaken the joint.

- Metallurgical Considerations: The microstructure of the weld metal and the heat-affected zone (HAZ) plays a crucial role in determining the mechanical properties of the joint. Careful control of cooling rates and heat input is necessary to avoid undesirable phases and grain growth.

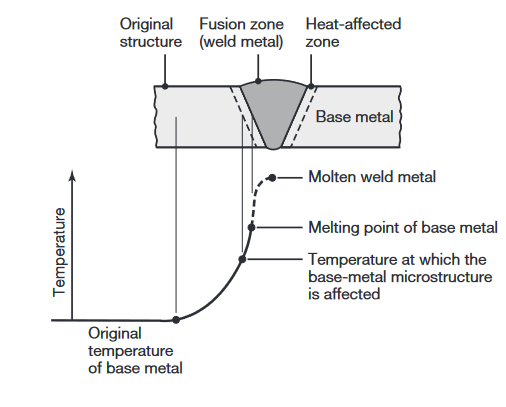

A typical fusion welded joint is shown in the following figure:

Characteristics of a typical fusion weld zone in oxyfuel gas welding and arc welding processes (Kalpakjian & Schmid, 2016).

Three distinct zones are identified:

- The base metal, the metal to be joined;

- The heat-affected zone (HAZ); and

- The fusion zone, the region that melts during welding.

After heat has been applied and the filler metal (if any) has been introduced into the weld zone, the molten weld begins to solidify and cool. The solidification process is similar to that in casting and begins with the formation of columnar (dendritic) grains; These grains are relatively long and form parallel to heat flow. Because metals are much better heat conductors than the surrounding air, the grains lie parallel to the plane of the two plates or sheets being welded.

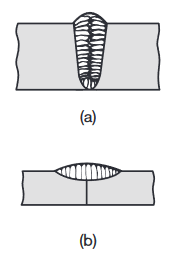

Grain structure in (a) a deep weld and (b) a shallow weld. Note that the grains in the solidified weld metal are perpendicular to their interface with the base metal.

The grains developed in a shallow weld are shown in the figure above (b).

The weld metal has a cast structure, and because it has cooled rather slowly, it typically has coarse grains; consequently, the metal has relatively low strength, hardness, toughness, and ductility. These properties can, however, be improved with proper selection of filler metal composition and with subsequent heat treatment of the joint.

Weld Quality

Because of its past history of thermal cycling and the attendant microstructural changes, a welded joint may develop discontinuities that can be caused by inadequate or careless application of established welding procedures or poor operator training. The major discontinuities that affect weld quality are described below:

-

Porosity in welds may be caused by (a) trapped gases that are released during melting of the weld zone but trapped during solidification of the weld zone; (b) chemical reactions that occur during welding; or (c) contaminants present in the weld zone.

-

Slag inclusions. These inclusions may be trapped in the weld zone. If the shielding gases used are not effective, contamination from the environment may contribute to slag inclusions.

-

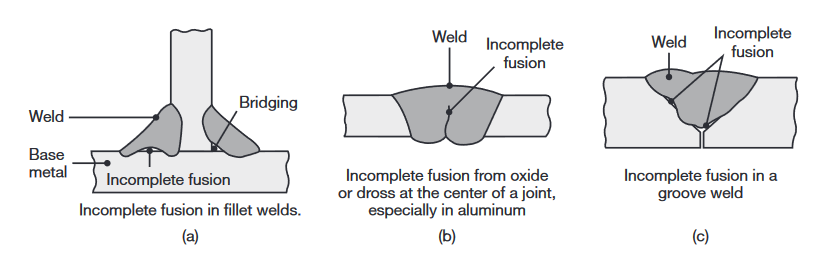

Incomplete fusion and incomplete penetration. Incomplete fusion (lack of fusion) produces poor weld beads, such as those shown in the following figure:

Examples of various incomplete fusion in welds.

-

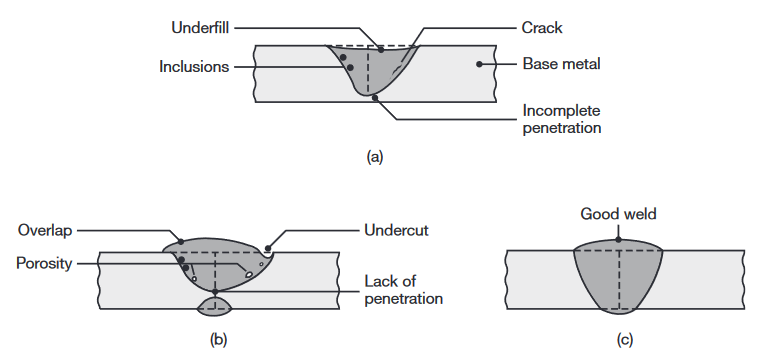

Weld profile. Weld profile is important not only because of its effects on the strength and appearance of the weld but also because it can indicate incomplete fusion or the presence of slag inclusions in multiplayer welds.

Examples of various defects in fusion welds.

-

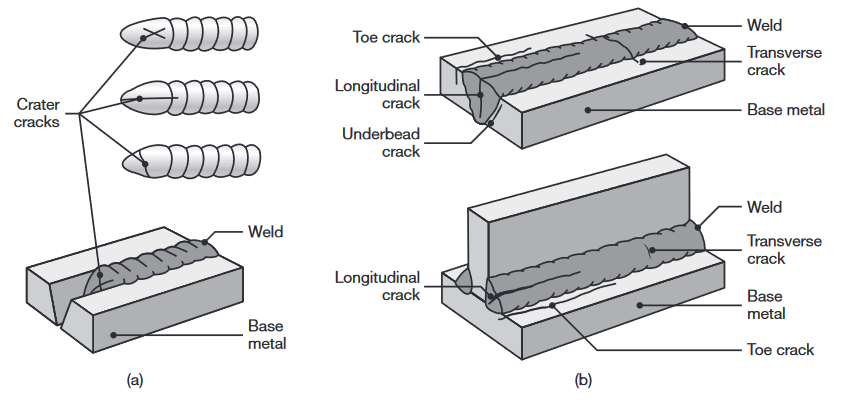

Cracks. Cracks may develop at various locations and directions in the weld zone. Cracks generally result from a combination of the following factors:

- Temperature gradients, causing thermal stresses in the weld zone;

- Variations in the composition of the weld zone, causing different contractions;

Types of cracks in welded joints. The cracks are caused by thermal stresses that develop during solidification and contraction of the weld bead and the welded structure.

Cracks are classified as hot cracks, developing while the joint is still at elevated temperatures, and cold cracks, that develop after the weld metal has solidified.

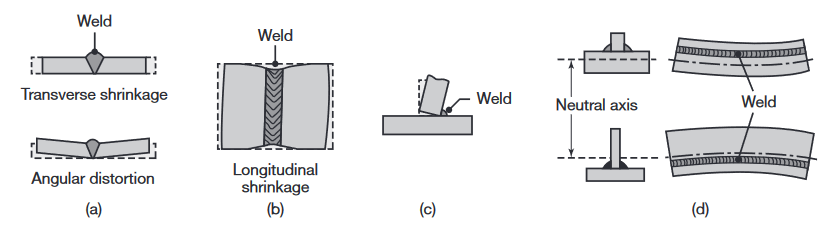

6. Residual stresses. Because of localized heating and cooling during welding, expansion and contraction of the weld area develop residual stresses.

>Distortion and warping of parts after welding, caused by differential thermal expansion and contraction of different regions of the welded assembly. Warping can be reduced or eliminated by proper weld design and fixturing prior to welding.

Weldability

Weldability is generally defined as (a) a metal’s capability to be welded into a specific structure with specific properties and characteristics and (b) the ability of the welded structure to satisfactorily meet service requirements.

The following list, in alphabetical order, briefly summarizes the weldability of specific groups of metals. Their weldability can vary significantly, with some requiring special welding techniques and proper control of all processing parameters.

- Aluminum alloys: weldable at a high rate of heat input; alloys containing zinc or copper generally are considered unweldable.

- Cast irons: generally weldable.

- Copper alloys: similar to that of aluminum alloys.

- Lead: weldable.

- Nickel alloys: weldable.

- Stainless steels: weldable.

- Steels, plain-carbon: (a) excellent weldability for low-carbon steels; (b) fair to good weldability for medium-carbon steels; and (c) poor weldability for high-carbon steels.

- Steels, low-alloy: fair to good weldability.

- Steels, high-alloy: generally good weldability under well-controlled

- Tin: weldable.

- Titanium alloys: weldable with the use of proper shielding gases.

- Zinc: difficult to weld; soldering preferred.