Introduction

From (Kalpakjian & Schmid, 2016):

Several methods can be used to shape materials into useful products. Casting is one of the oldest methods and was first used about 4000 B.C. to make ornaments, arrowheads and various other objects. The important factors in casting operation are:

- Solidification of the metal from its molten state, and accompanying shrinkage.

- Flow of the molten metal into the mold cavity.

- Heat transfer during solidification and cooling of the metal in the mold; and

- Mold material and its influence on the casting operation.

| Casting Process | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Sand casting | -Low cost | - Poor surface finish |

| - Versatile for complex shapes | - High degree of finishing required | |

| - Large components can be cast | - Lower dimensional accuracy | |

| Shell-Mold Casting | - Better surface finish than sand casting | - Higher cost than sand casting |

| - Higher dimensional accuracy | - Limited size of castings | |

| - Good for thin-walled sections | ||

| Lost Foam Process | - Complex and intricate shapes can be cast | - High cost of patterns |

| - Good surface finish | - Longer cycle times | |

| - Reduced need for cores | - Fragility of foam patterns | |

| Lost Wax Process | - Excellent surface finish and accuracy | - High cost of patterns and molds |

| - Suitable for complex and intricate shapes | - Time-consuming and labor-intensive process | |

| - Minimal machining required | ||

| Low-Pressure Permanent Casting | - Good mechanical properties due to controlled solidification | - Limited to relatively simple shapes |

| - Improved surface finish and dimensional accuracy | - Higher mold cost | |

| - Suitable for medium to high volume production | ||

| Die Casting (High-Pressure Casting) | - High production rate | - High initial cost for molds and machines |

| - Excellent surface finish and dimensional accuracy | - Limited to non-ferrous metals | |

| - Thin-walled sections can be cast | - High porosity levels |

Cast Structures

The type of cast structure developed during solidification of metals and alloys depends on the composition of the particular ally, the rate of heat transfer, and the flow of the liquid metal during the casting process.

Pure Metals

The typical grain structure of pure metal that has solidified in a square mold is shown in the following figure:

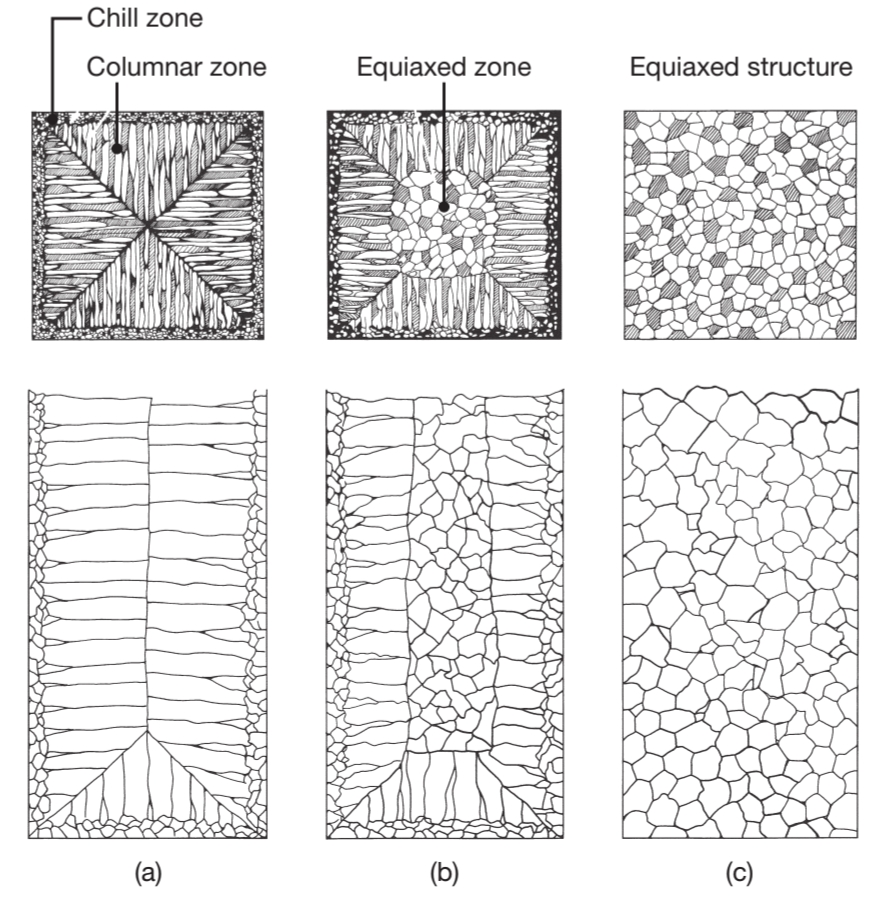

Schematic illustration of three cast structures of metals solidified in a square mold:

pure metals, with preferred texture at the cool mold wall. Note in the middle of the figure that only favorable oriented grains grow away the mold surface; solid-solution alloys; and structure obtained by heterogeneous nucleation of grains.

At the mold walls the metal cools rapidly (chill zone) because the walls are at ambient or slightly elevated temperature, and as a result, the casting develops a solidified skin (shell) of find equiaxed grains. The grains grow in the direction opposite to the heat transfer from the mold. Grains that have a favorable orientation, called columnar grains, grow preferentially.

Alloys

Because pure metals have limited mechanical properties, they are often enhanced and modified by alloying. The vast majority of metals used in engineering applications are some form of an alloy, defined as two or more chemical elements, at least one of which is a metal.

In Introduction to Material Engineering we have seen that solidification in alloys begins when the temprature drops below the liquidus,

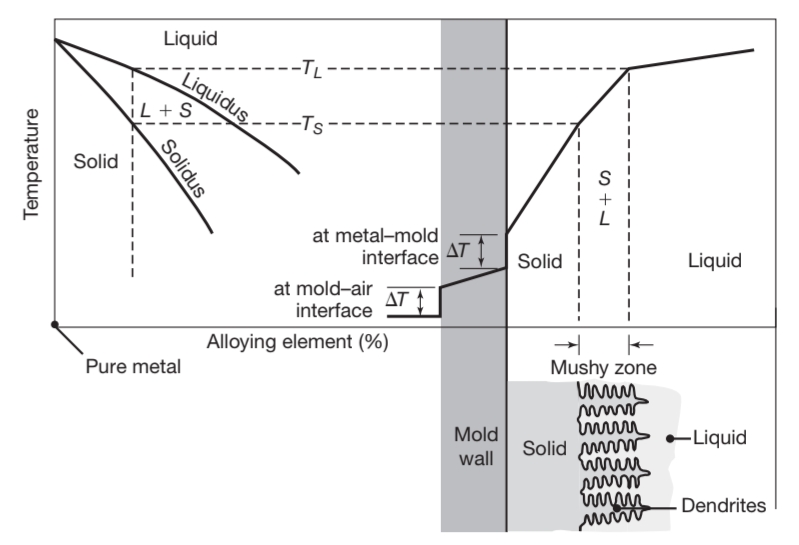

Schematic illustration of alloy solidification and temperature distribution in the solidifying metal. Note the formation of dendrites in the semi-solid (mushy) zone.

Note in the lower right of the figure the presence of liquid metal between the dendrite arms. Dendrites have three-dimensional arms and branches, which eventaully interlock, as shown in the next figure:

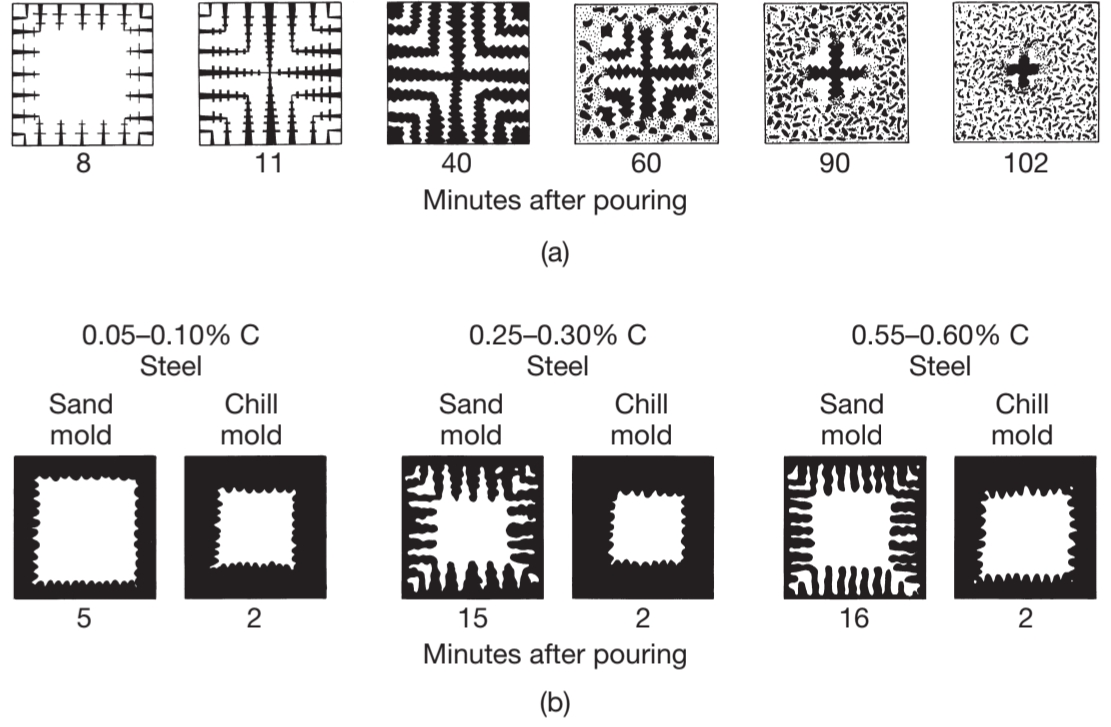

Solidification patterns for gray cast iron in a square casting. Note that after of cooling, dendrites reach other, but the casting is still mushy throught. It takes about two hours for this casting so solidify completely. Solidification of carbon steels in sand and chill (metal) molds. Note the difference in solidification patterns as the carbon content increases.

Slow cooling rate (on the order of

Structure-Property Relationships

Because all castings must possess certain specific properties to meet design and service requirements, the relationships between the properties and the structures developed during solidification are important considerations.

The compositions of dendrites and of the liquid metal in casting are given by the phase diagram of the particular alloy. Under normal cooling rates typically encountered in practice, cored dendrites are formed, which have a surface composition that is different from that at their centers. The surface has a higher concentration of alloying elements that at the core the dendrite, due to solute rejection from the core toward the surface during solidification of the dendrite (called microsegregation).

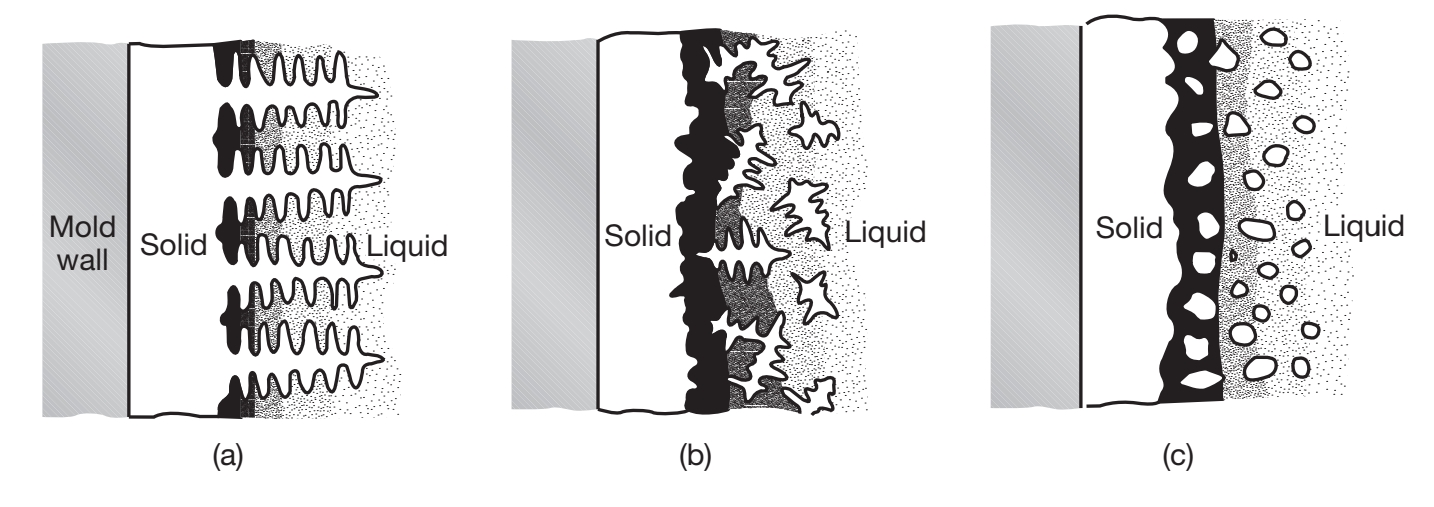

The darker shading in the interdendritic liquid near the dendrite shown in the following figure indicates that these regions have a higher solute concentration; consequently, microsegregation in these regions is much more pronounced than in others.

Schematic illustration of three basic types of cast structures: (a) columnar dendritic; (b) equiaxed dendritic; and (c) equiaxed nondendritic.

In contrast to microsegregation, macrosegregation involves differences in composition throughout the casting itself.

Heat Transfer

A major consideration in casting is the heat transfer during the complete cycle from pouring to solidification cooling of casting to room temperature. Heat flow at different location in the system depends on many factors, relating to the casting material and the mold and process parameters. For instance, in casting thin section, the metal flow rates must be high enough to avoid premature chilling and solidification. On the other hand, the flow rate must not be so high as to cause excessive turbulence.

Solidification Time

During the early states of solidification, a thin solidified skin begin to form at the cool mold walls; as time passes, the skin thickens. With flat mold walls, the thickness is proportional to the square root of time. Thus, doubling the time will make the skin

The solidification time is a function of the volume of a casting and its surface are (called Chvorinov’s rule), and is given by:

Where

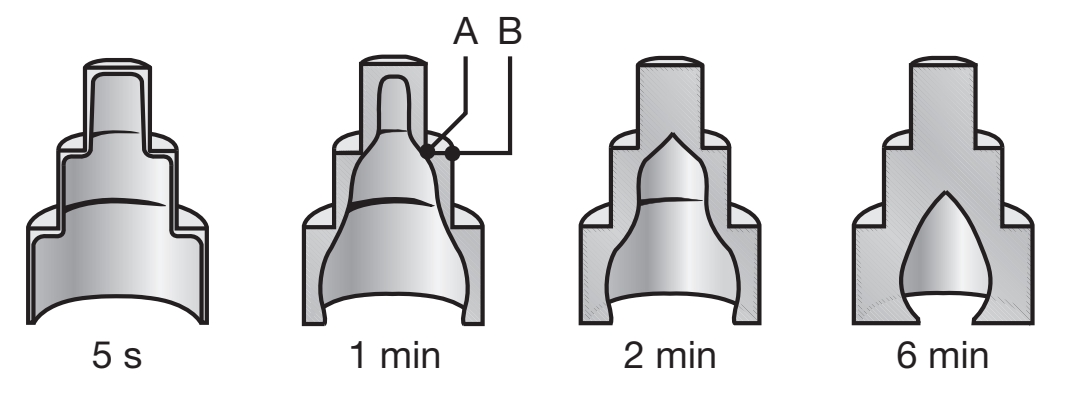

The effects of mold geometry and elapsed time on skin thickness and its shape are shown in the following figure:

Solidified skin on a steel casting; the remaining molten metal is poured out at the times indicated in the figure. Hollow ornamental and decorative objects are made by a process called slush casting, which is based on this principle.

The unsolidified molten metal has been poured from the mold at different time intervals, ranging from

Note that the skin thickness increases with elapsed time, and that the skin is thinner at the external angles. Note that this operation is very similar to making hollow chocolate candies in various shapes.

Shrinkage

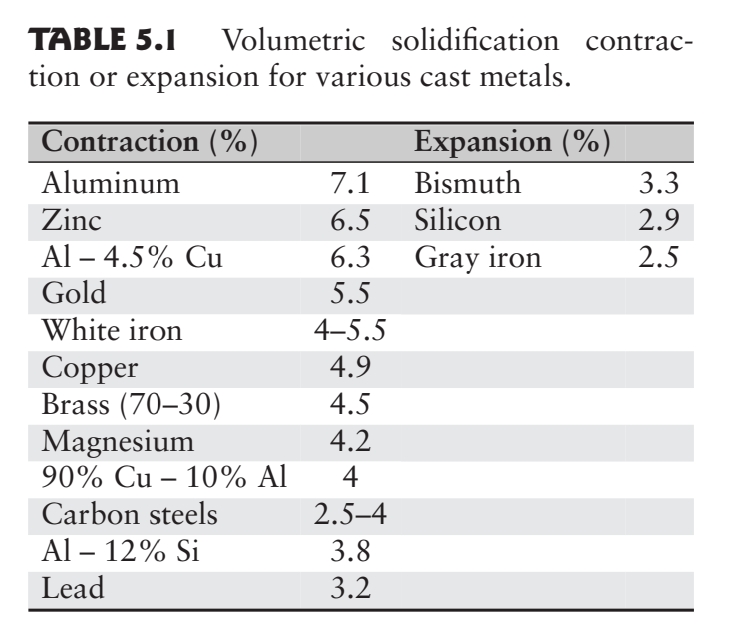

Metals generally shrink during solidification and cooling to room temprature:

Shrinkage in a casting causes dimensional changes and sometimes cracking and is a result of of the following phenomena:

- Contraction of the molten metal as it cools before it begins to solidify.

- Contraction of the metal during phase change from liquid to solid (latent heat of fusion).

- Contraction of the solidified metal (the casting) as its temperature drops to ambient temperature.

The largest potential amount of shrinkage occurs during the phase change of the material from liquid to solid; this can be reduced or eliminated through the use of risers or pressure-feeding of molten metal.

Note that some metals, such as gray cast iron, expand. The reason is that graphite has a relatively high specific volume, and when it precipitates as graphite flakes during solidification of the gray cast iron, it causes a net expansion of the metal.

Expendable-Mold, Permanent-Pattern Casting Processes

Casting processes are generally classified according to (a) mold materials; (b) molding processes; and (c) methods of feeding the mold with the molten metal. The two major categories are expendable-mold and permanent-mold casting. Expendable-mold processes are further categorized as permanent pattern and expendable pattern processes. Expendable molds typically are made of sand, plaster, ceramics, and similar materials, which generally are mixed with various binders or bonding agents.

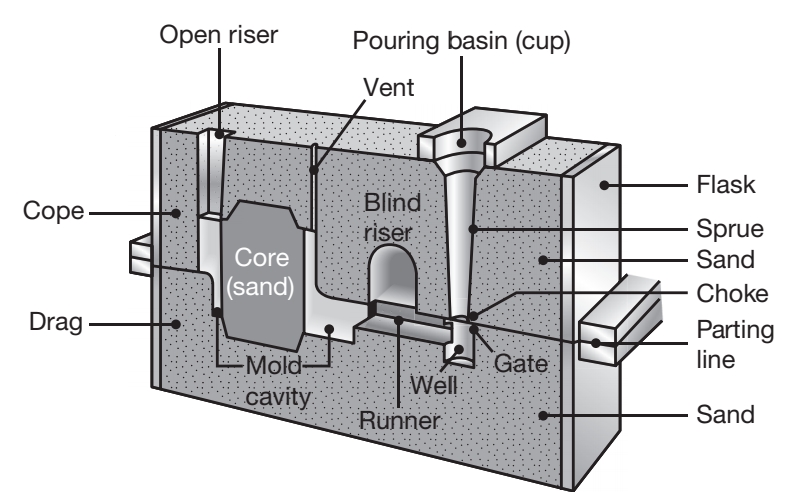

Sand casting

Cross section of a typical sand mold showing various features.

The sand casting process consists of (a) placing a pattern, having the shape of the desired casting, in sand to make an imprint; (b) incorporating a gating system; (c) filling the resuultin cavity with molten metal; (d) allowing the metal to solidify; (e) breaking away the sand mold; and (f) removing the casting and finishing it. Examples of parts made by sand casting are engine block, cylinder heads, machine-tool bases, and housings for pumps and motors.

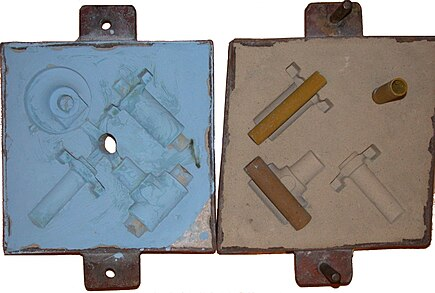

The cope and drag (top and bottom halves, respectively) of a sand mold, with cores in place on the drag.

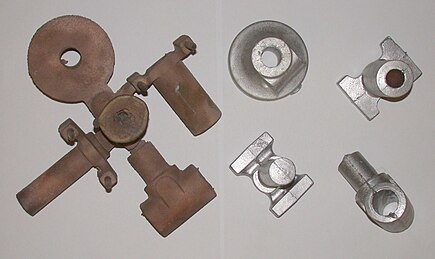

Two sets of castings (bronze and aluminum) from the above sand mold.

Shell-Mold Casting

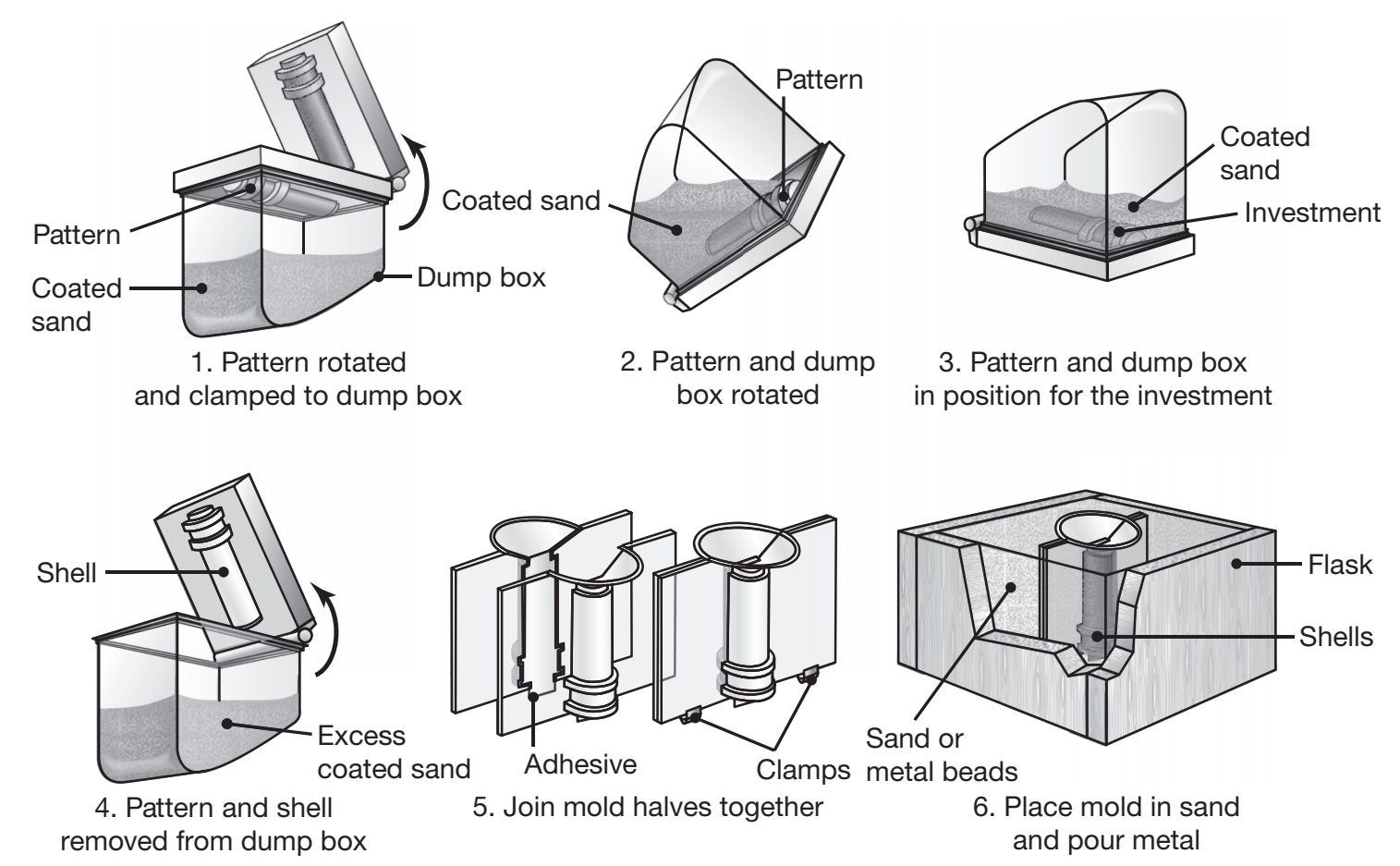

Shell-mold casting has grown significantly because it can produce many types of castings with close dimensional tolerances, good surface finish, and at a low cost. In this process, a mounted pattern, made of a ferrous metal or aluminum, is heated to

Schematic illustration of the shell-molding process, also called the dump-box technique.

The shells are light and thin, usually

Application include small mechanical parts requiring high precision, gear housings, cylinder heads, and connecting rods; the process is also widely used in producing high-precision molding cores, such as engine-block water jackets.

Expendable-Mold, Expendable-Pattern Casting Processes

Lost Foam Process

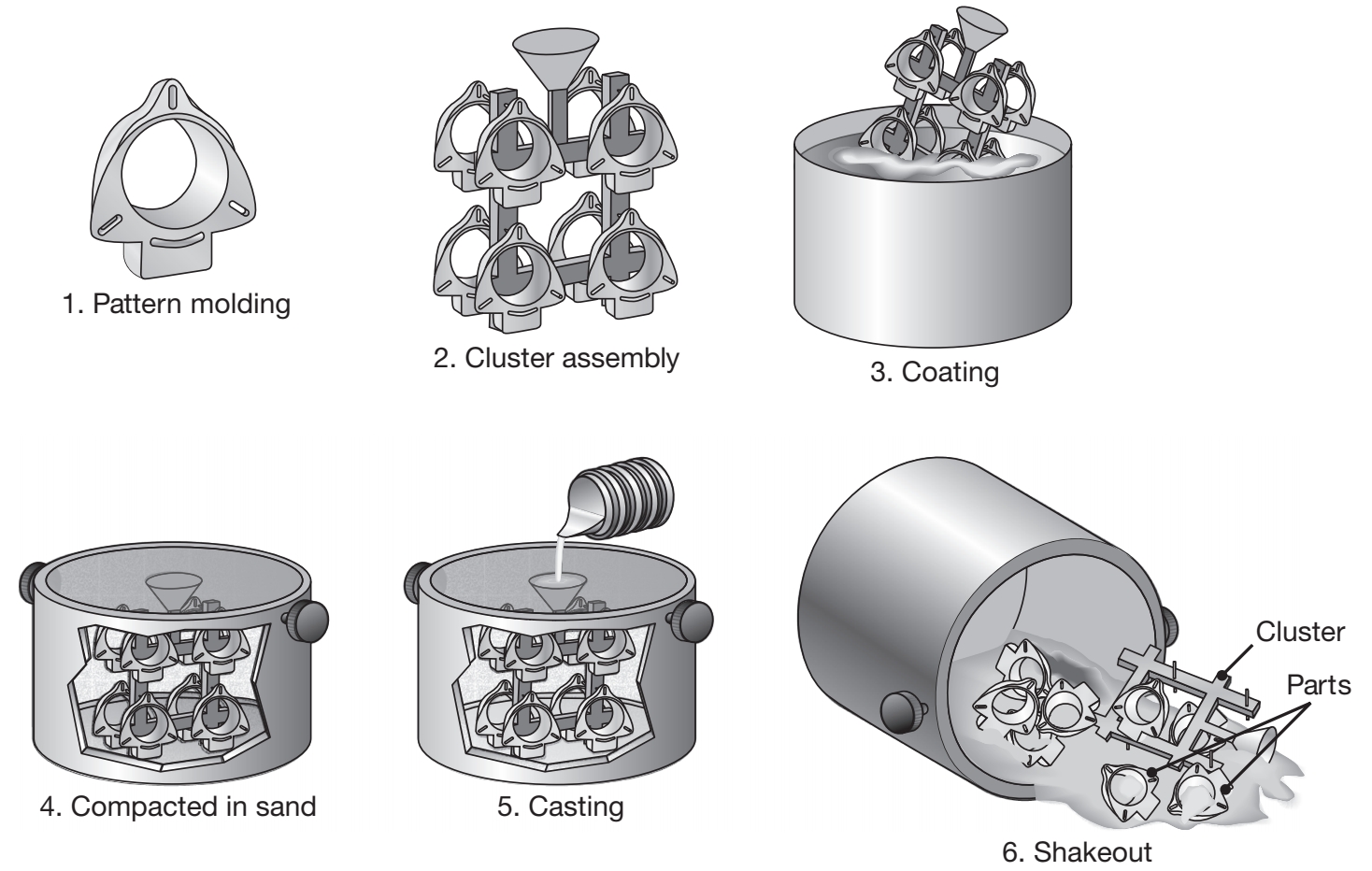

The expendable-pattern casting process uses a polystyrene pattern, which evaporates upon contact with the molten metal, to form a cavity for the casting.

Schematic illustration of the expendable-pattern casting process, also known as lost-foam or evaporative-pattern casting.

Typical parts made are aluminum engine blocks, cylinder heads, crank-shafts, brake components, manifolds, and machine bases.

Lost Wax Process

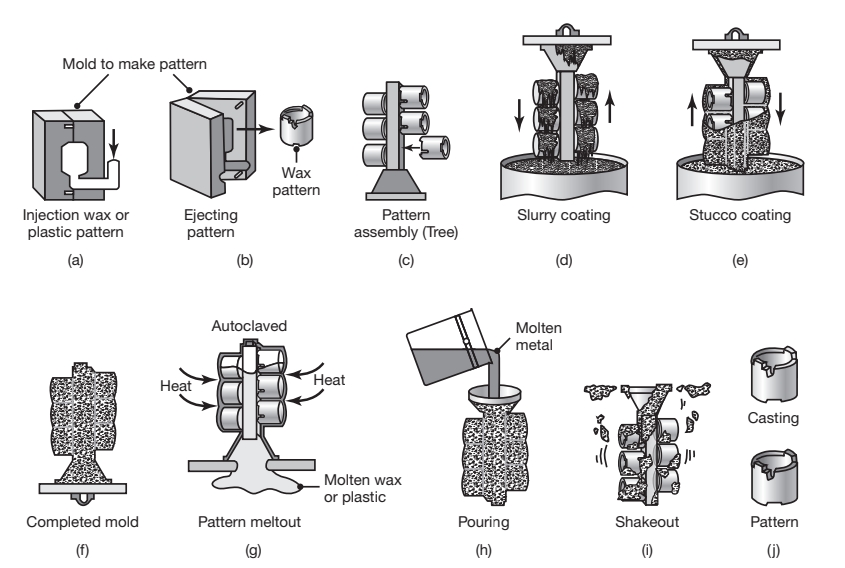

In the lost was process, typical parts made are mechanical components such as gears, cams, valves, and ratchets; The pattern is made by injecting semisolid or liquid wax or plastic into a metal die in the shape of the pattern, or is made through ad dive manufacturing methods. The pattern is then removed and dipped into a slurry of refractory material. After this initial coating has dried, the pattern is coated repeatedly to increase its thickness. The one-piece mold is dried in air and heated to a temperature of

Schematic illustration of investment casting (lost wax process).

Permanent-Mold Casting Processes

Permanent molds are used repeatedly and are designed so that the casting can be easily removed and the mold reused. The molds are made of metals that maintain their strength at high temperatures. Because metal molds are better heat conductors than expendable molds, described above, the solidifying casting is subjected to a higher rate of cooling. This, in turn, affects the microstructure and grain size within the casting.

Permanent mold casting.

Low-Pressure Permanent Casting

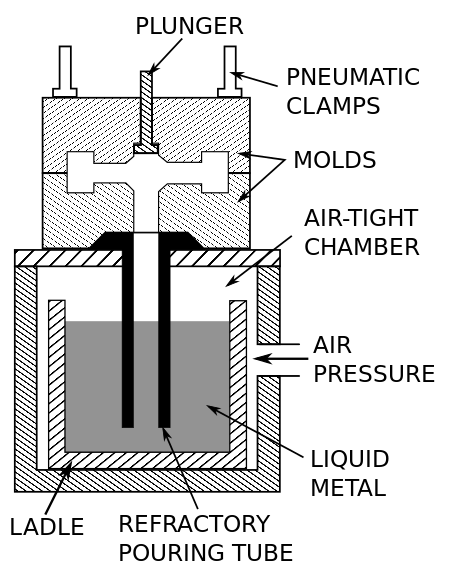

Low-Pressure permanent mold (LPPM) casting uses a gas at low pressure (

Schematic of the low-pressure permanent mold casting process

The pressure is applied to the top of the pool of liquid, which forces the molten metal up a refectory pouring tube and finally into the bottom of the mold.

Die Casting (High-Pressure Casting)

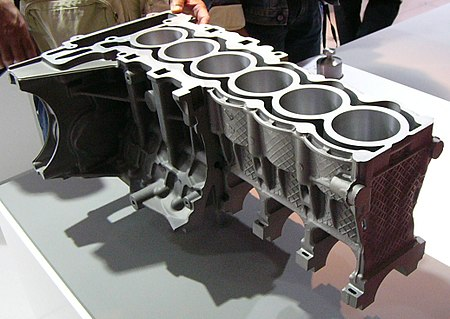

Die casting is a metal casting process that is characterized by forcing molten metal under high pressure into the die cavity at pressures ranging from

An engine block with aluminum and magnesium die castings.

Example:

What process should I choose for casting a large, simple-shaped component at a low cost?

Answer:

Sand casting would be the best choice due to its low cost and versatility for large components. However, be prepared for poorer surface finish and lower dimensional accuracy.

Example:

What casting process should be used for medium to high volume production with good mechanical properties and controlled solidification?

Answer:

Low pressure permanent mold casting is appropriate for medium to high volume production with good mechanical properties and controlled solidification. However, it is limited to relatively simple shapes and involves higher mold costs.