Introduction

From (Kalpakjian & Schmid, 2016):

In the manufacturing processes described in the preceding chapters, the raw materials used were either in a molten state or in solid form. This chapter describes groups of operations whereby metal powders, ceramics, and glasses are processed into products, as well as those involved in processing composite materials and superconductors.

The powder metallurgy (PM) process is capable of making complex parts by compacting metal powders in dies and sintering them (heating without melting) to net- or near-net-shape products.

Powder Metallurgy

One of the first uses of powder metallurgy was the tungsten filaments for incandescent light bulbs in the early 1900s.

Powder metallurgy has become competitive with processes such as casting, forging, and machining, particularly for relatively complex parts made of high-strength and hard alloys.

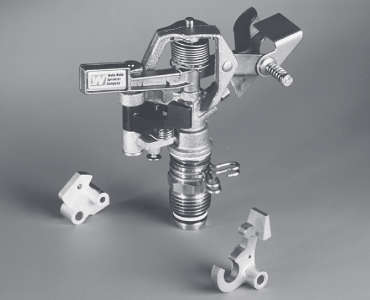

(top) Examples of typical parts made by powder-metallurgy processes. (bottom) Upper trip lever for a commercial irrigation sprinkler, made by PM. Made of unleaded brass alloy, it replaces a die-cast part, at a 60% cost savings. Source: Metal Powder Industries Federation.

Production of Metal Powders

Metal powders can be produced by several methods, the choice of which depends on the particular requirements of the end product. Sources for metals generally are their bulk form, ores, salts, and other compounds. These forms are then produced, by various methods, into powders.

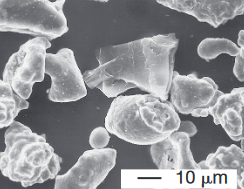

(top) Scanning-electron microscope image of iron powder particles made by atomization. (bottom) Nickelbased superalloy (Udimet 700) powder particles made by the rotating electrode process; Source: P.G Nash.

One method of powder production is Atomization:

Atomization produces a liquid-metal stream by injecting molten metal through a small orifice. The stream is broken up by jets of inert gas, air, or water, known as gas or water atomization, respectively.

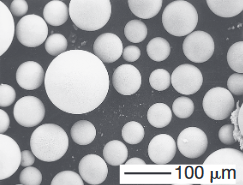

Particle shapes and characteristics of metal powders and the processes by which they are produced. (Kalpakjian & Schmid, 2016).

Compaction of Metal Powders

Compaction is the step in which the blended powders are pressed into specific shapes using dies and presses that are either hydraulically or mechanically actuated.

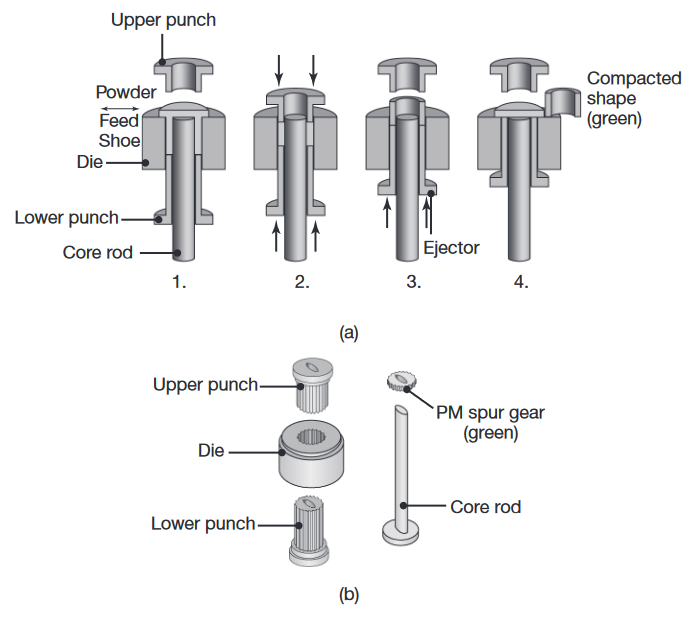

(a) Compaction of metal powder to produce a bushing. (b) A typical tool and die set for compacting a spur gear. Source: Metal Powder Industries Federation.

The purposes of compaction are to obtain the required shape, density, and particle-to-particle contact, and to make the part sufficiently strong to be handled and processed further.

Density is relevant during three different stages in PM processing: (a) as loose powder; (b) as a green compact; and (c) after sintering.

Porosity

The particle shape, average size, and size distribution all affect the packing density of loose powder. An important factor in density is the size distribution of the particles. If all of the particles are of the same size, there will always be some porosity when packed together. Theoretically, the porosity is at least

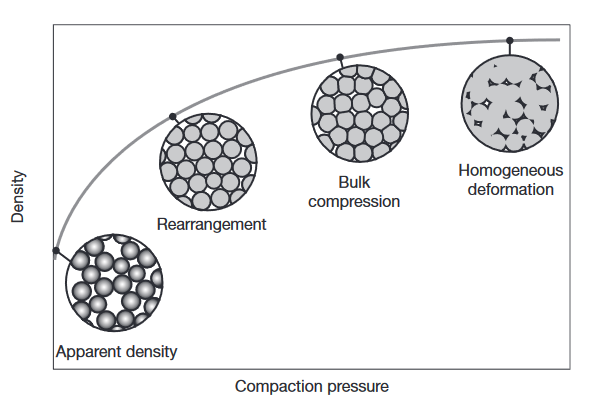

Compaction of metal powders: at low pressures, the powder rearranges without deforming, leading to a high rate of density increase. Once the powders are more closely packed, plastic deformation occurs at their interfaces, leading to further density increases but at lower rates. At very high densities, the powder behaves like a bulk solid.

Isostatic Pressing

For improved compaction, PM parts may be subjected to a number of additional operations, such as rolling, forging, and isostatic pressing. Because the density of die-compacted powders can vary significantly, powders can be subjected to hydrostatic pressure in order to achieve more uniform compaction.

In cold isostatic pressing (CIP), the assembly is pressurized hydrostatically in a chamber, usually filled with water. The most common pressure is

In hot isostatic pressing (HIP), the container is usually made of a high melting-point sheet metal, and the pressurizing medium is inert gas or vitreous (glasslike) fluid. typical operating condition for HIP is

In Pressure-less compaction, the die is filled with metal powder by gravity, and the powder is sintered directly in the die. Because of the resulting low density, pressure-less compaction is used principally for porous parts, such as filters.

Sintering

Sintering is the process whereby compressed metal powder is heated in a controlled-atmosphere furnace to a temperature below its melting point, but sufficiently high to allow bonding (fusion) of the individual metal particles.

Sintering mechanisms

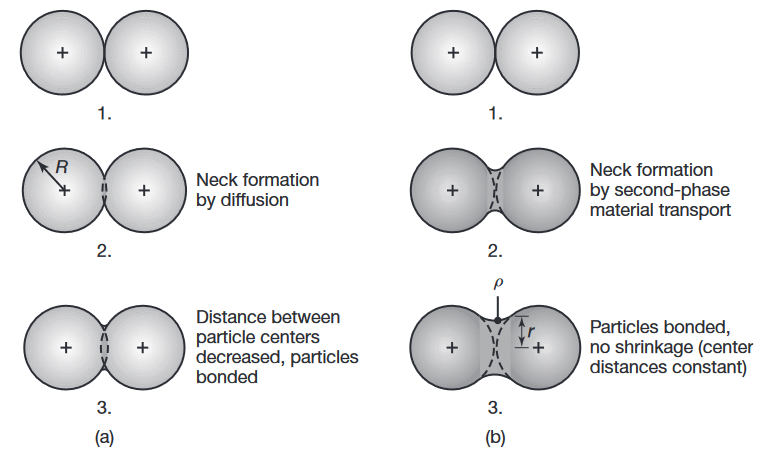

Sintering mechanisms are complex and depend on the composition of the metal particles as well as the processing parameters. As the temperature increases, two adjacent particles begin to form or strengthen a bond by diffusion (solid-state bonding), as shown in the following figure:

Schematic illustration of two basic mechanisms in sintering metal powders: (a) solid-state material transport and (b) liquid-phase material transport.

is the particle radius, is the neck radius, and is the neck profile radius.

As a result, the strength, density, ductility, and thermal and electrical conductivities of the compact increase. At the same time, however, the compact shrinks, hence allowances should be made for shrinkage, as is done in casting.

Ceramics: Structure, Properties, and Applications

Ceramics are compounds of metallic and nonmetallic elements. The term ceramics refers both to the material and to the ceramic product itself.

Some properties of ceramics are significantly better than those of metals, particularly their hardness and thermal and electrical resistance. Ceramics are available as single crystal or in polycrystalline form.

Grain size has a major influence on the properties of ceramics; the finer the size, the higher is the strength and the toughness (fine ceramics).

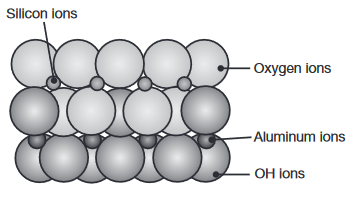

The crystal structure of kaolinite, commonly known as clay. (Kalpakjian & Schmid, 2016).

General Properties and Applications of Ceramics

Compared with metals, ceramics have the following general characteristics: brittleness, high strength and hardness at elevated temperatures, high elastic modulus, low toughness, low density, low thermal expansion, and low thermal and electrical conductivity. However, because of the wide variety of compositions and grain size, the mechanical and physical properties of ceramics can vary significantly.

Because of their sensitivity to cracks, impurities, and porosity, ceramics’ strength in tension is approximately one order of magnitude lower than their compressive strength. Such defects lead to the initiation and propagation of cracks, under tensile stresses, severely reducing tensile strength.

Tensile strength:

The tensile strength of polycrystalline ceramic parts increases with decreasing grain size and increasing porosity. Common earthenware, for example, has a porosity of

where

Modulus of elasticity:

The modulus of elasticity of polycrystalline ceramic is affected by porosity, as given by:

where

Thermal conductivity

Ceramics’ thermal conductivity varies by as much as three orders of magnitude, depending on composition, whereas the thermal conductivity of metals varies by one order of magnitude. Also, as with other materials, thermal conductivity decreases with increasing temperature and porosity (because air is a very poor thermal conductor).

The thermal conductivity, k, is related to porosity by

where

Exercises

Question 1

Completely dense ceramic material has a tensile strength

Solution:

According to General Properties and Applications of Ceramics:

Question 2

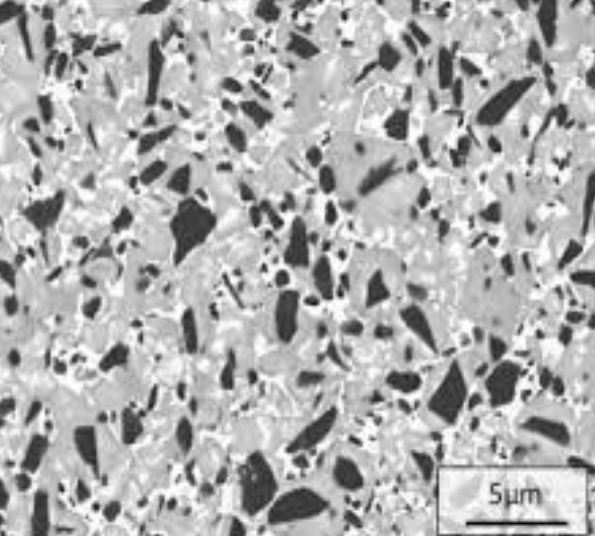

Consider the following microstructures of sintered cemented carbide (Co/WC) used as a machining tool and discuss on:

- Porosity level in the material

- Estimated level of its mechanical properties: hardness (sufficient/insufficient), flexural strength (sufficient/insufficient)

- Sintering type (pressure-assisted / pressure-less) applied

- Operating sintering applied temperature.

Cemented carbide (Co/WC). We will denote the top microstructure with the letter A and the bottom one with the letter B.

Solution:

- A - high porosity (more than

).

B - low, almost zero porosity. - A - low hardness and insufficient flexural strength.

B - high hardness and acceptable flexural strength. - A - pressure-less sintering.

B - pressure assisted sintering. - A - insufficiently low (less than

).

B - sufficient (high asapproximately)